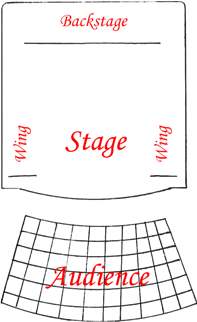

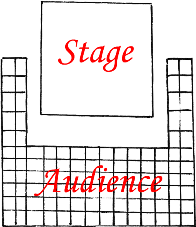

Proscenium

| Fig. 1 |

|

Proscenium theatre arrangement,

drawn by Rev. Michael J Dangler |

Proscenium arrangements are designed to provide “windows” into the action on the stage: the audience is therefore “outside” the action, looking in. The entire action takes place within the forward view of the audience member, and the audience is “in it together,” meaning that they are all observing the same thing with the same backdrop. Additionally, there are places outside the view of the audience: the areas backstage and in the wings that are generally obscured from the audience’s view, either via curtains or scenery. (Figure 1, right)

Major advantages provided by this configuration include a high level of control over what is seen and heard by the attendees; the ability to have a “backstage area” where people can prepare to do roles or set up and store props; a definite clarity of roles (everyone knows who is a “performer” and who is an audience member); and it is highly scalable, allowing to no set upward limit (excepting space and sound projection limits) to attendance.

Because this is the way we watch most theatre plays (and all movies), this type of arrangement leads to a few particular disadvantages. The first major disadvantage is a definite “performance” feeling for those watching: audience participation is minimized in this type of configuration. Mainstream churches (particularly mega-churches) are set up in this format most often: it is by far the most effective way of providing ritual to large numbers of people all at once. Still another disadvantage is that there are often issues with “line of sight” and the creation of “bad seats” where a person in a particular seat may not be able to see everything that is happening.

The primary disadvantage that a Grove will encounter is the “church-like” feel of this configuration. The primary way to avoid this is not to engage this configuration until the limitations of the “thrust” configuration are overwhelming the disadvantages of the proscenium configuration. Engaging the congregation in roles and direct participation are also good ways to reduce the “church-like” feel.

Line-of-sight issues and bad seats can be minimized by keeping visual obstacles to a minimum, and increasing the apron of the stage to give the arrangement more thrust. Also, using ritual spaces already designed for this style of performance (rather than attempting this without a stage or a rise to the seats) can also help minimize these issues. Ensuring that the performers project toward the audience and do not turn their back on them is also vital.

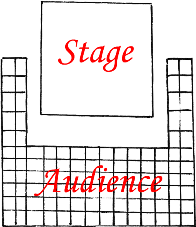

Thrust

| Fig. 2 |

|

Thrust theatre arrangement,

drawn by Rev. Michael J Dangler |

The term “thrust” comes from the notion that this configuration “thrusts” the actor into the audience: it can be generally described as a configuration where the audience is arranged around the stage, which is usually completely visible except from behind (or nearly behind). (Figure 2, right)

The primary advantages of this configuration include a more intimate feel (the audience feels more a part of what is going on, partially because the audience is also in their field of vision: either across from them or to their side). Additionally, this configuration reduces barriers: there are no wings to the stage, and there are rarely curtains or other visual blocks, meaning that prop and setting changes are rarer. Because the audience is so close to the actors, there is less of a “performance” feel to rituals in this configuration, and it feels less like “church” to most attendees, because it does not match the experiences they had of church growing up.

The primary disadvantages include reduced projection options: in this configuration, the speaker will be in profile to (or turned away from entirely) at least half the audience at any given time. In addition, because there is less access to off-stage area, changing the setup of the ritual area is more complicated, and there is a smaller staging area for the next speaker to prepare in. Altars and props must have greater dimensionality (they must be “presentable” from several other directions, rather than just in a “straight-on” view) since the audience can now see at least three sides of any object.

Mitigating these disadvantages is generally not too complicated: by training ritualists where to project their voice to (and to teach them to treat all areas of the audience the same), the projection issues can be reduced. For particularly large groups, microphones and amplifiers can go a long way. Storage of props can be best mitigated through preparation: either placing them in the charge of the ritualist who will use them, or finding space on the altar. Longer altar cloths can hide many imperfections in setup (such as cheap altar tables) and flowers or other decorations can hide imperfections on props until they are needed.

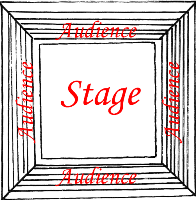

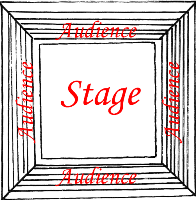

Theatre-in-the-Round (Arena)

| Fig. 3 |

|

Arena theatre arrangement,

drawn by Rev. Michael J Dangler |

Theatre in the Round (or Arena) has only one particular advantage: it is the most intimate of the three configurations. Here, the theatre is set up in such a way as to have the audience on all sides of the stage, usually in bleacher-style seating. (Figure 3 at right)

This configuration works only in very small groups (roughly no more than 9-13 in my experience) and is best suited for rituals where parts are chosen at random and on the spot (e.g. going around a circle and doing the next part as it comes up rather than assigning the parts in advance). For rituals of this size, where the participants truly are comfortable being intimate, the disadvantages are negated by size.

Those disadvantages begin to quickly rear their head as soon as you exceed the upper limits of the round configuration, however. This form of theatre configuration places extreme limits on projection: no matter what you do, you will always have roughly half the audience to your back, or out of your line of sight. This means that no matter what you do to project, at least half the people there will not hear what you have to say. Additionally, there is no prop storage, meaning that you cannot place anything outside of the sight of the ritual attendees, because someone will have a view of it.

If forced to work in an arena configuration, the best thing to do is to turn it into a thrust if at all possible. That means moving the altar to one end of the ritual space and placing all celebrants at that end as well. Doing this can keep the intimate feel of the circle for most participants, and the “wall of celebrants” can remain behind the speaker and form the “backstage” area where there is no audience. While this leaves the celebrants out of the rite as participants, it creates a better experience for everyone else in attendance, who can now hear and see everything you are doing.

Works Cited

- Ionazzi, Daniel A. The Stagecraft Handbook. Betterway Books : Cincinnatti, OH. 1996.